This op-ed included contributions from Futurum Senior Analyst Oliver Blanchard

Just a few days ago, on January 24th, the EC’s antitrust commission fined Qualcomm 997 Million € (or US$ 1.2 Billion) for allegedly “abusing its dominant market position in the LTE chipset space to prevent rivals from competing in the market.” A year ago, before Futurum started taking an interest in Qualcomm’s business and peeling back its layers, that sort of ruling from the EC would have hardly been a blip on my radar. The EC, after all, has a history of going after non-European tech companies, especially if they are based in the US, and finding reasons to harass and fine them. But something about the ruling immediately raised a red flag with me. For starters, Qualcomm doesn’t really enjoy a “dominant market position” in the LTE chipset space. Qualcomm just has better LTE chipsets than its rivals, which is a very different thing.

(Whether you want to argue that Qualcomm’s LTE chipsets are better than everyone else’s or that Qualcomm manages to develop and releases next gen LTE chipsets faster than its competitors, is moot. What matters here is that Qualcomm’s competitive advantage is, by definition, neither anticompetitive nor is it the result of anticompetitive behaviors. Qualcomm has, over the years, lost market share to its rivals when they were able to field competitive products and solutions. That is how healthy competitive markets behave.)

So, upon hearing that the EC’s antitrust commission had ruled that Qualcomm had somehow abused its “dominant market position” to “prevent rivals from competing in the LTE chipset space,” all kinds of alarm bells started going off in the back of my head. It just didn’t sound right. It wasn’t until I noticed that the case involved a complaint from Apple though, that my spider senses started really tingling. Before we get to Apple’s part in this, let’s circle back to the EC’s habit of targeting non-European tech companies with investigations and fines, because it’s important to understand the role that dynamic may have played in this case.

Are the EC and the EU engaging in protectionist behaviors?

It can be difficult to categorically say one way or the other if countries, regions, and their appointed regulatory agencies engage in protectionist schemes. All you can do is watch what they say and do, look for patterns, and draw your own conclusions. From where I am standing however, the EC does appear to show a tendency towards protectionism. Not to the extent that China and Korea seem to pursue protectionist policies, but they do fall somewhere on the protectionist spectrum. For the record, I don’t think that’s necessarily a bad thing. A little protectionism doesn’t hurt. It’s all about turf, after all. If regulatory agencies didn’t flex their muscles once in a while, or crack the whip, even, very large companies with a lot of cash on hand and significant political clout might forget who’s really in charge of enforcing antitrust and anticompetitive laws, for instance. Fair enough.

Like it or not, there is a certain logic to this model, and most of the time, it doesn’t discriminate: Google is treated just like Facebook. IBM is treated just like Amazon. Apple is treated just like Samsung. Everyone takes a turn at the whipping post, and everyone gets roughly the same number of lashes (proportionate to company size). Factor it as a cost of doing business in a particular market: Take your whipping and pay the gatekeepers on your way through. We’ve written about this before. Bad behavior – and particularly anticompetitive behavior – doesn’t appear to be a prerequisite when it comes to adverse rulings and subsequent fines issued by the EC. Sometimes, it’s a factor, but not always. One after the other, the likes of Google, Intel, Microsoft, Samsung, and now Qualcomm have taken turns being raked over the coals by the EC, regardless of their guilt

When you take a step back and look at the EC’s behaviors from that perspective, an EC ruling against Qualcomm was to be expected at some point. The commission appears to have been looking for a way to nail Qualcomm to its whipping post for a long time. Two previous attempts immediately come to mind: Nokia (and several other vendors’) complaint to the EC in 2005, accusing Qualcomm of anticompetitive behaviors, and Icera’s complaint against Qualcomm in 2010. Though the latter is still technically “ongoing” after nearly 8 years, neither case has, to date, turned up definitive evidence against Qualcomm. After 13 years of frustrated attempts and no results, it isn’t difficult to see why the EC might have been eager to find another case it could throw at Qualcomm. Whether Apple approached the EC or the EC approached Apple is immaterial, at least to the purposes of our discussion. If my hunch is correct, and the EC was looking for a way to score some kind of win against Qualcomm, any complaint against the company would have been likely to catch the commission’s attention, and so here we are.

The question that keeps nagging at me though, is this: Did the EC stumble onto Apple’s complaint and decide to use it to achieve its own ends? Or did Apple, grasping the value of its complaints to regulators eager to blood their whips, so to speak, find a way to weaponize them to strike at its competitors? It’s a theory gaining traction in some analyst circles. If true, it’s clever. Insidious and Machiavellian, but clever. And the inescapable irony here is that, if this is indeed what happened, the EC may have inadvertently allowed itself to get roped into an anticompetive scheme in an effort to allegedly crack down on anticompetitive behaviors.

Either way, the commission certainly does appear to have missed the mark on a few very important elements of this case. Let’s get into them:

What did the EC’s antitrust commission get wrong in its case against Qualcomm?

First, let’s look at the claims made in the EC’s rulings:

- “Qualcomm illegally shut out rivals from the market for LTE baseband chipsets for over five years, thereby cementing its market dominance.

- Qualcomm paid billions of US Dollars to a key customer, Apple, so that it would not buy from rivals. These payments were not just reductions in price – they were made on the condition that Apple would exclusively use Qualcomm’s baseband chipsets in all its iPhones and iPads.

- This meant that no rival could effectively challenge Qualcomm in this market,no matter how good their products were.

- Qualcomm’s behaviour denied consumers and other companies more choice and innovation – and this in a sector with a huge demand and potential for innovative technologies. This is illegal under EU antitrust rules and why we have taken today’s decision.”

A few questions immediately come to mind:

- What did the agreement defining conditions for Apple’s chip purchase from Qualcomm actually say?

- Was there any evidence in this “Transition Agreement” or from the companies’ negotiations, that Qualcomm forced Apple to buy its chips?

- Is it reasonable to expect that anyone, including the European Commission, can force Apple to do anything Apple doesn’t want to do?

Let’s address the commission’s four points:

- There is no evidence that Qualcomm “shut out rivals” for even five minutes, let alone for over five years. As this claim is entirely predicated on Qualcomm forcing Apple to agree to anticompetitive terms, let’s table that for a moment and jump right to item number 2.

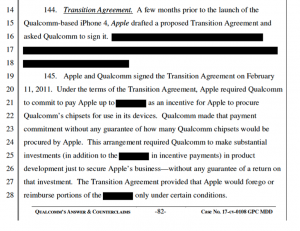

- For those not familiar with the lengthy and historically, generally healthy relationship between Qualcomm and Apple (at least until 2016), here’s a quick synopsis of the early days: Apple initially developed the iPhone with Qualcomm IP used under licenses owned by Apple’s contract manufacturers; Apple chose, however, to use modems from Infineon (bought by Intel in 20xx) until the iPhone 4s, when it decided to switch to Qualcomm’s modems. This migration from Infineon to Qualcomm was the focus of the “Transition Agreement” drafted by Apple, in which it laid out conditions for designing Qualcomm modems into its products.

Qualcomm claims that Apple not only initiated the transaction, but it also required Qualcomm to pay it an incentive so that it would purchase chipsets from Qualcomm and use them in the iPhone.

That appears to be true, but don’t take my word for it: In its counterclaim filed in US Federal Court last April (shared below), Qualcomm noted that its agreement with Apple required Qualcomm, at Apple’s request, to provide Apple with financial incentives in the form of payments, to essentially subsidize Apple’s purchases of Qualcomm chipsets. This in no way constitutes Qualcomm forcing Apple to buy anything. Instead, it shows Apple’s intent to purchase Qualcomm chipsets, Apple’s own terms under which these purchases would take place, and Apple exerting its buying power by requiring a supplier to agree to Apple’s demands for significantly lower pricing. (If this behavior seems familiar, you have been paying attention: It is what Apple also appears to be doing with licensing: Exerting its market power to pressure Qualcomm into “agreeing” to much lower rates.)

It is also worth noting that the agreement also required Qualcomm to make substantial investments in product development to create a product that could only be used by Apple with no guarantee of any volume of purchase whatsoever. No minimums. No quotas.

Question: If Apple dictated the terms of its agreement with Qualcomm to Qualcomm, how can the commission rule that Qualcomm exerted its “dominant position” in the LTE chipset market to prevent its rivals from competing?

But that question, however relevant to the case and the ruling, is moot, and here is why: The terms of the agreement did not require Apple to deal exclusively with Qualcomm.

In other words, no part of the agreement forced Apple to buy chipsets from Qualcomm, to buy minimum quantities of chipsets from Qualcomm, or in any way block Apple from buying chipsets from other vendors.

In other words, the commission’s contention that “Qualcomm illegally shut out rivals from the market for LTE baseband chipsets for over five years” and that “Qualcomm paid billions of US Dollars to a key customer, Apple, so that it would not buy from rivals – made on the condition that Apple would exclusively use Qualcomm’s baseband chipsets in all its iPhones and iPads” are demonstrably false.

Item number 3: “This meant that no rival could effectively challenge Qualcomm in this market, no matter how good their products were.” This contention being mostly predicated on items one and two, which are invalid, is consequently false as well: There existed no mechanism by which Qualcomm’s rivals were unable to compete for Apple’s business.

The commission also offers no material evidence that rival of Qualcomm were indeed kept from challenging Qualcomm “no matter how good their products were.” If there is evidence that Intel or other chipset makers were shut out, I haven’t seen it. But it gets worse: The commission’s argument is invalidated by the fact that Apple began sourcing chipsets from Intel for the iPhone 7 while the agreement was still in effect.

Item number 4: “Qualcomm’s behaviour denied consumers and other companies more choice and innovation.” Again, nothing in Qualcomm’s “behavior” suggests that it denied consumers and other companies more choice and innovation, and the commission fails to make a case for this argument as well.

Who is really bullying whom?

Now that we have addressed what the agreement defining the terms of Apple’s agreement with Qualcomm actually said, found no any evidence that Qualcomm forced Apple to buy anything, and that consequently, Qualcomm did not, in fact, engage in anticompetitive behaviors, let’s quickly address our final question: Is it reasonable to expect that anyone, including the European Commission, can force Apple to do anything Apple doesn’t want to do?

Qualcomm, as a company, is literally 1/10th the market cap of Apple. Even if we were to completely ignore the facts we just outlined, and pretended that Qualcomm wanted to pressure Apple, a company with virtually unlimited resources and market power, into an agreement it didn’t want to enter into, there is no conceivable way that it could.

When has Apple ever been compelled to do anything it didn’t want to do by one of its suppliers? Name one instance since Apple became the largest tech company in the world in which one of its suppliers bullied it into doing something it didn’t want to do.

The commission’s argument is that Qualcomm, a much smaller company than Apple, and whose rivals offer equally competitive products (“no matter how good their products were,” per the commission’s ruling) was somehow able to do exactly that, even though in that scenario, it would have taken nothing for Apple to walk away from Qualcomm and go do business with those rivals instead. What “market dominance” is the commission talking about when the company claiming to have been bullied by Qualcomm is as powerful as Apple?

Not only is there no material evidence to back up the claim, it doesn’t even make logical sense. To add insult to injury, the EC knows better: as powerful as the commission is, it cannot even get Apple to pay taxes for business done in Europe. It stands to reason that if even the EC can’t make Apple pay taxes, Qualcomm can’t exactly force Apple to buy chipsets it doesn’t want. Now pause with me and take a big whiff: does it smell fishy to you too?

How could the EC possibly have gotten this one so wrong? Your guess is as good as mine.

In conclusion…

Let’s recap:

- The basis of an anti-trust case against Qualcomm is that Qualcomm allegedly used its dominant position to cause harm to competition in a market. Based on the material evidence I have reviewed, Qualcomm doesn’t appear to have had a reason or a motive to do this, or the power to do it. Furthermore, Qualcomm doesn’t appear to have even attempted to.

- The commission seems unaware that since, at the time of the complaint, there existed no alternative or comparable product for Apple to purchase in place of Qualcomm’s chipsets, Apple’s agreement with Qualcomm could not have harmed another vendor (or dis-incentivized Apple to use another product, because there wasn’t one).

- Alternatives to Qualcomm’s products eventually appeared when other companies finally managed to catch up, proving that Qualcomm’s actions did not, in fact, keep companies from competing in the LTE chipset market.

- When these alternatives became available, Apple began sourcing chipsets from Intel for the iPhone 7 (while the transition agreement was in effect). This alone should be enough to invalidate Apple’s complaint, and subsequently the case against Qualcomm.

- With regard to competition, the market was already competitive before the commission’s investigation was opened. Vendors other than Qualcomm were developing competitive LTE chips. They were simply slower to get their chipsets to the market than Qualcomm. This is the nature of competition. There is nothing nefarious about it.

- Bear in mind that the commission’s ruling has not changed the competitive dynamic of the market in Europe. The market is just as competitive today as it was when the investigation was opened. Curiously, aside from the fine imposed on Qualcomm, I see no attempt by the commission to drive a course correction in the competitive ecosystem that it argues was being harmed by Qualcomm.

- The market will still be competitive after Qualcomm pays this fine, and the competitive dynamic will not have changed as a result of it. (The commission’s ruling and fine won’t, for example, make Intel’s chipsets more competitive.)

- The EC failed to show how Qualcomm’s actions caused harm to consumers. I would argue that the opposite is true: Competition between Intel and Qualcomm pushed both companies to develop increasingly better chipsets, which consumers benefitted from. As Apple eventually sourced iPhone 7 chipsets from both Qualcomm and Intel, I would further argue that consumers did indeed benefit from more rather than fewer choices, as the commission erroneously alleges.

- Finally, if Qualcomm was in as powerful position as Apple and the commission claim, why would it have agreed to pay Apple, at Apple’s request, incentives to use its products? Wouldn’t Qualcomm have had the power to make more demands on Apple than the other way around? (If not on price, at least on minimum quantities?) Since when does the party with the most power allow the party with the least power to dictate the terms of an agreement between them? Think about that for as long as you need.

Here’s what seems to have happened: Two big companies worked together to find an agreement that would benefit both. After some reflection, one of these companies, with a lot more influence and money than the other – influence over everything, everywhere – decided that it could turn against the other and gain an even greater advantage, and get away with it. And so here we are. Simple enough. What troubles me though, is that in its zeal to go after Qualcomm, the commission seems to have not only failed to spot the obvious problems with Apple’s complaint, but also (and the irony should be lost on no one) failed to push back against what, some might argue, seems to be yet another attempt by Apple to use its dominant market position to force suppliers to bend to its will. While Apple does not technically enjoy a monopsony in the smartphone market, it certainly has the ability to behave like it does. The commission should probably start getting wise to that dynamic. If, as some of my peers have begun to suggest, large regulatory bodies (like the EC) can be weaponized by a handful of companies big enough and clever enough to hack the system in their favor, if the institutions we rely on to keep these companies in check (regulators and the courts) can no longer be trusted to do their job, where do things go from here? Perhaps more importantly, who will those companies, working through their oblivious proxies, go after next? It isn’t a trivial question.

Qualcomm, obviously, plans to appeal.

Photo: Press conference by Margrethe Vestager, Member of the EC: EC fines Qualcomm €997 million for abuse of dominant market position

Date: 24/01/2018. Location: Brussels – EC/Berlaymont

© European Union , 2018. Source: EC – Audiovisual Service. Photo: Mauro Bottaro

Disclosure: Fatty Fish is a research and advisory firm that engages or has engaged in research, analysis, and advisory services with many technology companies, including those mentioned in this article. The author does not hold any equity positions with any company mentioned in this article.

The original version of this article was first published on Futurum Research.

Daniel Newman is the Principal Analyst of Futurum Research and the CEO of Broadsuite Media Group. Living his life at the intersection of people and technology, Daniel works with the world’s largest technology brands exploring Digital Transformation and how it is influencing the enterprise.

-

Daniel Newmanhttps://staging-fattyfish.kinsta.cloud/author/danielnewman/September 29, 2022

-

Daniel Newmanhttps://staging-fattyfish.kinsta.cloud/author/danielnewman/August 26, 2022

-

Daniel Newmanhttps://staging-fattyfish.kinsta.cloud/author/danielnewman/June 30, 2022

-

Daniel Newmanhttps://staging-fattyfish.kinsta.cloud/author/danielnewman/June 28, 2022